Intervertebral disc herniation or slipped disc

In dogs, slipped discs (also known as intervertebral disc herniation) are the most common cause of paralysis, but in cats it is much less common. Although the reason for this difference is unclear, it may be due to the disc’s composition.

The spinal cord is contained within the vertebrae of the spine; the vertebral column. There are many nerves in the spinal cord (like the wires in an electrical cable), which connect the brain to the peripheral nervous system, which controls movements of the limbs and other functions. There is a spongy, doughnut-shaped pad between the vertebrae called an intervertebral disc (IVD). The IVD lies just beneath the spinal cord. In addition to providing stability and support, it allows movement of the spine and distributes loads among the vertebrae. It consists of two parts: an inner semi-liquid centre, called the nucleus pulposus, and an outer ligament, called the annulus fibrosus, which contains the nucleus.

What is a slipped disc?

Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) is a condition caused by aging or degenerative processes (e.g. premature aging). Although disc problems are age-related, at-risk individuals can suffer them at an early age. As the nucleus ages, the proteins-sugars and water content change. As a result of these changes, the outer annulus becomes weakened, making it stiff and brittle. When a disc degenerates, it is less able to provide stability and support to the spine.

There are different clinical syndromes associated with disc disease in animals:

Type-I disc disease occurs when degenerate nuclear material is extruded from a torn annulus – like jam coming out of a doughnut. Degeneration of the nucleus must precede stiffening of the disc as the once semi-liquid centre becomes dry and loses its cushioning properties. This can cause the ligament (annulus fibrosus) to tear, allowing the nucleus to leak out and put pressure on the spinal cord (disc extrusion). Dogs of all breeds and ages can be affected by this sudden onset disease, but it most frequently affects young (2–6 years) small breed dogs. The condition occurs mostly in chondrodystrophic or dwarf breeds, e.g. Pekingese, Basset Hounds, French Bulldogs, Dachshunds, etc.

In type-II disc disease, the outer ligament (annulus fibrosus) protrudes or bulges over time. Thickening is thought to occur due to ligament tears over time, and as the ligament repairs itself it thickens (a process called hypertrophy). As the dorsal part of the annulus fibrosus thickens, it presses up against the spinal cord (disc protrusion). The lower neck, mid-back, and lower back are the regions of the spinal column that are more likely to experience disc degeneration. This is a slowly progressive condition that most often affects dogs and cats 5-12 years old of mid to large breeds

Acute non-compressive nucleus pulposus extrusion (ANNPE), also known as traumatic disc or type-III disc, occurs suddenly. Typically, this occurs with heavy exercise or trauma, causing a healthy disc with a normal nucleus to rupture from a sudden tear in the ligament. Since the material that explodes out along the vertebral canal appears to dissipate along the spinal cord, the injury to the spinal cord does not result in on-going spinal cord compression.

Disc cysts or hydrated nucleus pulposus extrusions (HNPE) are a final form of disc disease that are very similar to Type-I disc disease. The major difference here is that no degeneration of the semi-liquid centre (i.e. the nucleus pulposus) of the disc occurs and so this material leaks out of the ligament (annulus fibrosus) and compresses the spinal cord.

What are the signs of a slipped disc?

Disc disease is most commonly associated with spinal pain. Spinal pain causes a pet to adopt abnormal posture (low head carriage, rounding of the back), to be reluctant to move or exercise, and to cry when moving around. Pressure from a slipped disc can damage the nerves and cause symptoms. Blood can also leak into the spine if the disc slips suddenly, putting even more pressure on the nerves. Symptoms include a loss of coordination, weakness, paralysis, lameness, faecal or urinary incontinence, and loss of feeling in the legs.

How do I know how severe the slipped disc is?

The signs that develop following disc damage are the result of:

- Compression of the spinal cord by the herniated disc material (compression component).

- Bruising of the spinal cord caused by the impact of the disc as it is herniate (concussion component).

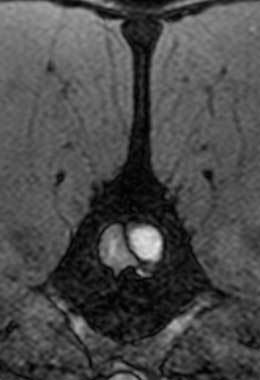

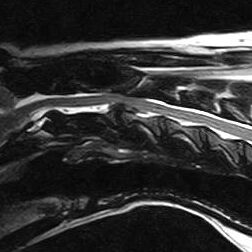

By examining an animal alone, it is impossible to determine how much of each component contributes to the signs. A myelogram, CT scan, or MRI can be used to determine the extent of spinal cord compression. The amount of bruising can, however, be extremely difficult to assess (even with specialised techniques). This concussion can sometimes be seen as spinal cord swelling.

Cables that make up the spinal cord are organised according to their functions within the nervous system. The most superficial cables are those running from the leg to the brain. Their main purpose is to transmit information about the location of the leg and body to the brain. Since these nerves are the most superficial, they are the first to be affected by disc pressure. Damage to these nerves results in the animal being wobbly or appearing drunk on their legs.

As we move deeper into the spinal cord, we reach the next group of cables that send messages to the legs from the brain. When these cables are damaged, the legs become weak and may eventually become paralysed. Among the deepest spinal cord cables are those that inform the brain of bladder fullness, and those delivering pain signals from the limbs to the brain. When these cables are not functioning, the animal is unable to urinate and becomes unable to feel its own toes.

As nerve fibres flow from the brain to the muscle along the spinal cord, the clinical signs will refer to spinal cord dysfunction ‘down-stream’ of the injury – hence disc disease in the lower back can cause hind limb weakness, paralysis or urinary incontinence – disc disease in the neck can cause weakness on all limbs. There is a possibility that a slipped disc can cause lameness if it traps one of the spinal nerves as it exits the spine.

Injuries to the spinal cord vary in severity, and they are graded according to their severity:

| Grade | Clinical Signs |

| 1 | Pain only |

| 2 | Walking with weakness and drunkenness in the back legs |

| 3 | Loss of ability to walk with some movements still in the legs |

| 4 | Paralysis with no movement in the legs |

| 5 | Paralysis with loss of feeling when a painful stimulus is applied to the toes |

When an animal recovers from a spinal injury, their nerve functions return in reverse order.

How do I diagnose a slipped disc?

A full neurological examination will be needed if a pet shows any signs of back problems or lameness.

Standard X-rays are rarely enough to diagnose a slipped disc. In a standard X-ray, only the bones of the vertebrae are visible, not the discs between them or the spinal cord. Conventional X-rays can sometimes reveal disc degeneration without the animal showing any symptoms. Only myelography (X-rays taken after injection of dye around the spinal cord), CT (computed tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can reliably diagnose a slipped disc. Tests such as these help to determine whether there is a slipped disc, where it is located, and if there are any other causes of spinal pain or paralysis.

Will the pet need an operation?

The severity of the condition, the rate at which the condition is progressing, and the presence of severe pain determine whether medical or surgical treatment is recommended. In imaging studies, the appearance of the disc problem may also be helpful. Most of the time, a slipped disc is considered a surgical disease, unless:

- The animal has never experienced back pain before.

- Anaesthesia for the animal is contraindicated due to a medical condition.

- If the animal has minimal spinal cord compression and it is suspected that spinal bruising is causing most of the symptoms.

- Following an ANNPE and sometimes a HNPE. Medical treatment is often recommended in this case.

The primary goal of medical or non-surgical treatment is to reduce pain and inflammation. Some disc problems can be treated by the body’s own immune system by forming scar tissue over the annulus to make them more inert, less inflammatory, and less compressive. Usually, non-surgical treatment involves strict rest, in a cage or room depending on a pet’s size, for at least 4 weeks with drugs that reduce inflammation and pain. In order to ensure that a pet is not getting worse without surgery, you may want to see them on a regular basis. The aim of this rest is to allow the torn ligament (the annulus fibrosus) to heal and 4-6 weeks of rest are advised as we know this is the time it takes for ligaments to heal. Even when medical treatment is successful, there is a 50% chance that a pet will relapse in the future.

How can an operation help the pet?

Surgery involves drilling a hole in the vertebrae to remove the part of the IVD that is pressing on the spinal cord. The recovery period varies from one week to four weeks.

In surgery, the compressive element of the disc is removed by making a hole in the spinal column. Surgery is usually required quickly for Type-I disease and on an elective basis for Type-II disease if neurologic dysfunction develops or if pain is severe. For milder forms of HNPE and ANNPE, surgery is not required. Surgery carries a small risk of causing further trauma, but it should prevent further deterioration and relapse. Success of surgery depends mainly on how much spinal cord function has been lost and especially whether or not and for how long the pet has lost the ability to feel pain in its toes. Most animals with pain sensation have a very good prognosis. There is a 50:50 chance that paralysed dogs with no pain sensation in their rear legs will recover the ability to walk if the sensation was lost within the last 12 hours. As soon as this time has passed, the prognosis becomes very grave.

Will the pet recover without surgery?

No matter what the cause of the disc disease, the prognosis for recovery is dependent on the severity of the injury to the spinal cord. In particular, the ability to perceive deep pain applied to the toes (also known as nociception) indicates that some nerve fibres still send information back and forth and that the spinal cord can recover. It is essential to operate on animals with Type-I disc disease who lose ‘deep-pain’ as soon as possible in order to prevent them from becoming permanently disabled. There is no definite rate or extent of recovery and it is difficult to predict. It is possible for animals with mild spinal cord injuries to recover quickly and fully. Severe injuries can also be treated in this way, but it can take a lot longer. Despite carrying a small risk of causing further trauma, surgery should prevent further deterioration and relapse in the future.

A full recovery may be less likely in animals with Type-II disc disease because it can result in more long-term degenerative changes to the spinal cord and its blood supply. Treatment aims to preserve spinal cord function, prevent pain, or make pain more responsive to oral medication.

It is possible for disc disease to recur in an affected animal. It is estimated that around 10% of dogs with disc disease will experience a recurrence in the future.